This had been a great week for cycle racing in Britain. It was announced on Friday 14th December that Yorkshire has won the bid for the Tour De France Grand Depart. The first two stages will take place in Yorkshire and a third will finish in London before the race transfers to France. This is an enormous coup for Yorkshire and Britain. Then, to cap it all, Bradley Wiggins wins the BBC Sports Personality of the Year yesterday, Sunday 16th, and Dave Brailsford (Cycling GB and Team Sky) was voted top coach of the year. The rise of cycling’s success and profile in recent years is evidenced by Mark Cavendish winning in 2011 (Tour De France sprinter’s green jersey and the World Road Race champion) and Chris Hoy in 2008 (3 track golds in the Olympics). Previous to this we have to go back to 1967 when Beryl Burton (World Road Race champion and 12 hour TT national record for both men and women) came second to Henry Cooper and Tom Simpson came first in 1965 (World Road Race champion).

So, I look forward with relish to the 2014 Tour De France. But what will transpire then will undoubtedly be influenced by what happens in 2013, in particular the Wiggins/Froome controversy. After Froome appeared to sacrifice his own chance of winning the Tour De France last year Wiggins stated that in 2013 he would ride for Froome as pay-back. Earlier this year he said that he did not intend to defend his yellow jersey as he wanted to concentrate on the Giro, the Tour of Italy. This precedes the Tour De France and, assuming Bradley wins it, would leave him to support Froome in the French Tour. Part of the controversy was due to the fact that Froome was clearly the better climber and, if nothing else, certainly sacrificed a stage win to help Wiggins. But Wiggins was the better time trialist, crucial for this year’s event, and Froome lost time to Wiggins very early due to getting caught out in a crash. My view, for what it is worth, is that Wiggins was the more complete rider and worthy winner. The vow to support Froome in 2013, the yellow jersey riding as a domestique for an arguably less able team mate, did not ring true for many of us. Sure enough, apparently on the back of some good numbers in early training, Wiggins appears to be changing his mind and now says he wants to defend his jersey in 2013. Does this mean Sky will have two leaders who will fight it out? Or will Dave Brailsford have to decide who it will be and order one to ride for the other? I want to see Bradley ride for a second win but I will feel sorry for Froome if he is ordered to ride for him again. I would not be surprised if Froome, after his showing in the mountains and his eventual second to Wiggins, did not receive lucrative offers and unambiguous leadership for the Tour from other teams and sponsors. But with a team and resources like Sky and the promise of Wiggins riding for him, why would Froome think twice about any other offers? Perhaps he should have learnt the lesson of the 1986 Tour and the similar situation Greg Lemond found himself in with his team leader Bernard Hinault, the Badger.

In 1985 Greg Lemond was riding for Bernard Hinault to help him win his 5th Tour De France and equal the records of Jacques Anquetil and Eddy Merckx. Hinault had not had a particularly good year running up to the Tour, recovering from a knee operation, but seemed in good form at the start. Lemond and the rest of the La Vie Claire team (created in 1984 around Hinault specifically to secure his 5th win) were controlling the stages and chasing any significant breakaways so that Hinault could conserve energy for the crucial mountain stages, where he would take time from the other main contender, and the time trials where he would deliver the coup de grace. However, on the 16th stage Hinault crashed in the last kilometre and suffered a badly broken nose . He struggled across the line several minutes later but was awarded the same time as the bunch he was in. Lemond was in a small group he had been policing that had sprinted for the stage victory a short time before the main field finished. Over the following days, while Hinault was nursed along by his team mates, Lemond continued to police and follow the elite riders who were attacking Hinault and riding for the overall win. As the next few days unfolded it became clear that Lemond was the equal of any of them. Had he ridden to aid them rather than merely to defend Hinault’s interests he could have worn yellow into Paris with Hinault hanging on for the third step of the podium. On the crucial day, when he asked permission to do this, Lemond was led to believe Hinault was not far behind and catching, so he sat up and waited. It was only as time passed that Lemond realised the true position and his one opportunity to be the first American to win the Tour De France had gone. Hinault continued to recover over the remaining days and rode into Paris with the yellow jersey and his 5th record equalling win. And it was on the podium, during the yellow jersey ceremony, that he announced to the world and to Lemond on the step beside him (who finished second only 1 minute and 42 seconds behind) that next year he would be riding for Lemond’s victory, a message he repeated on a number of occasions at press conferences over the next few weeks.

In 1985 Greg Lemond was riding for Bernard Hinault to help him win his 5th Tour De France and equal the records of Jacques Anquetil and Eddy Merckx. Hinault had not had a particularly good year running up to the Tour, recovering from a knee operation, but seemed in good form at the start. Lemond and the rest of the La Vie Claire team (created in 1984 around Hinault specifically to secure his 5th win) were controlling the stages and chasing any significant breakaways so that Hinault could conserve energy for the crucial mountain stages, where he would take time from the other main contender, and the time trials where he would deliver the coup de grace. However, on the 16th stage Hinault crashed in the last kilometre and suffered a badly broken nose . He struggled across the line several minutes later but was awarded the same time as the bunch he was in. Lemond was in a small group he had been policing that had sprinted for the stage victory a short time before the main field finished. Over the following days, while Hinault was nursed along by his team mates, Lemond continued to police and follow the elite riders who were attacking Hinault and riding for the overall win. As the next few days unfolded it became clear that Lemond was the equal of any of them. Had he ridden to aid them rather than merely to defend Hinault’s interests he could have worn yellow into Paris with Hinault hanging on for the third step of the podium. On the crucial day, when he asked permission to do this, Lemond was led to believe Hinault was not far behind and catching, so he sat up and waited. It was only as time passed that Lemond realised the true position and his one opportunity to be the first American to win the Tour De France had gone. Hinault continued to recover over the remaining days and rode into Paris with the yellow jersey and his 5th record equalling win. And it was on the podium, during the yellow jersey ceremony, that he announced to the world and to Lemond on the step beside him (who finished second only 1 minute and 42 seconds behind) that next year he would be riding for Lemond’s victory, a message he repeated on a number of occasions at press conferences over the next few weeks.

However, the French media and public could not and did not believe that their beloved Badger would not attempt a 6th victory to take the all time record. 1986 would probably be his only chance of making history as he had vowed to retire that year as age and injuries were catching up with him. And, in any case, tradition decreed that if at all possible the yellow jersey should always be defended out of respect to the race and to its history. Working to aid an American winner was unthinkable given the strong anti-american feeling of the French public and media. All the papers assumed that the battle for the win would be between two Frenchmen, Hinault the defending champion and the winner of 1983 and 84, Laurent Fignon, returning after a year out recovering from the Achilles heel operation that effectively finished his career. Lemond barely got a mention and was not seen as a serious contender. No one realised at the time that Hinault’s victory of 1985 would be the last by a Frenchman to this day.

Indeed, Hinault seemed to be having second thoughts. As the early season wore on, particularly as Lemond was not having great success that year so far, partly because of lack of enthusiasm from some of the team members, Hinault made a number of statements along the lines of ‘we will let the race decide who is strongest’ and, out of respect for the Tour ‘I will ensure if Lemond wins he will have deserved it’ and so on. When it came to the race Hinault appeared to take every opportunity to attack Lemond. He was only 2 seconds ahead in the prologue time trial, took another 2 seconds in stage 1, but another 44 seconds from him in the 61.5 km Individual Time Trial at Nantes. So far Hinault looked the fitter rider. The crunch came on the 217.5 km stage 12 in the Pyrenees, Bayonne to Pau, when Hinault finished 3 minutes 36 seconds ahead of Lemond. The pair were now first and second on general classification with Hinault leading by 5 minutes and 25 seconds. Was this game over?

Far from it. The next stage 14 was the horrific 186 km from Pau to Superbagnères taking in the major ascents of the Tourmalet, Aspin, Peyresourde and Superbagnères. Hinault, a very volatile person at the best of times and perhaps in a moment of madness, attacked on the descent of the Tourmalet and continued the attack up the the Aspin where, at the top, he had a further 2 minutes and 20 seconds over Lemond. However, he was caught and dropped on the final climb of the Superbagnères where Lemond won the stage and took back from Hinault exactly the amount of time he had lost to him the previous day. Hinault was still in yellow but that night the merde really hit the fan in the La Vie Claire team. It was on stage 17 in the Alps that Lemond at last got in front of Hinault to wear the yellow jersey as Tour leader. He did this by the ‘simple’ expedient of sitting on the third placed contender, ZImmerman, when he attacked and dropped Hinault. At the stage finish Hinault was in third place 2 minutes and 47 seconds behind Lemond.

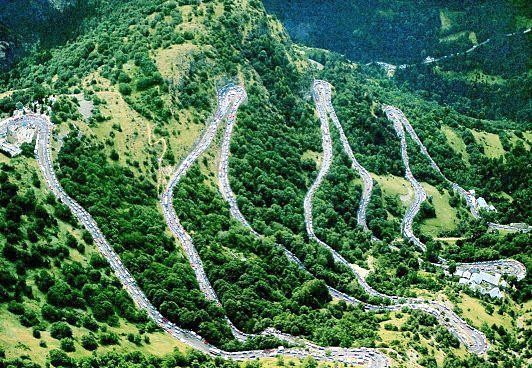

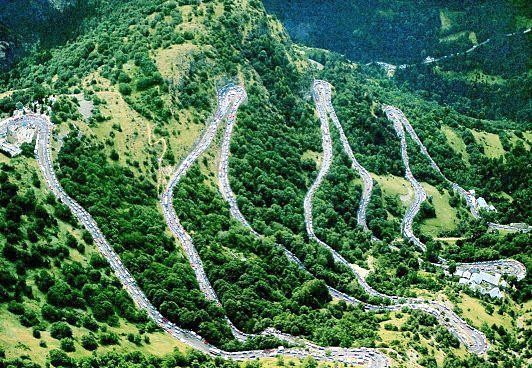

Perhaps the most remarkable stage of that year’s Tour was the stage 18 which climbed the Galibier and Croix de Fer before finishing at the top of the notorious 21 hair pins of L’Alpe d’Huez. Hinault and Lemond finished side by side in the same time, Lemond apparently pushing Hinault over the line to take the stage victory as a (perhaps rather ironic) thank you.

Perhaps the most remarkable stage of that year’s Tour was the stage 18 which climbed the Galibier and Croix de Fer before finishing at the top of the notorious 21 hair pins of L’Alpe d’Huez. Hinault and Lemond finished side by side in the same time, Lemond apparently pushing Hinault over the line to take the stage victory as a (perhaps rather ironic) thank you.  What had started as a battle between the two up L’Alpe d’Huez left the rest of the field and main contenders in tatters with the nearest over 5 minutes behind and the rest in gasping disarray over the 13.8 km of average 8% slopes with maximums of 12%. The contest between to two had effectively, and deservedly, given Lemond the overall victory, all others simply blown away. His 2 minutes 45 second lead overall on Hinault should be enough to withstand the challenge of Hinault in the final time trial which in the event Hinault won with Lemond 25 seconds behind in second place – even though he had crashed, remounted and rode with a rubbing brake until he could change his bike. So for the first time the Tour De France was won by an American. And, as Hinault said when he began to prevaricate on his promise to support Lemond, the race did decide who the strongest rider was although no doubt he felt sure the verdict would be in his favour. Hinault retired at the end of the season, as he said he would, and went on to devote his life to his farm in Brittany and various duties connected to the Tour De France. And France still awaits another French hero.

What had started as a battle between the two up L’Alpe d’Huez left the rest of the field and main contenders in tatters with the nearest over 5 minutes behind and the rest in gasping disarray over the 13.8 km of average 8% slopes with maximums of 12%. The contest between to two had effectively, and deservedly, given Lemond the overall victory, all others simply blown away. His 2 minutes 45 second lead overall on Hinault should be enough to withstand the challenge of Hinault in the final time trial which in the event Hinault won with Lemond 25 seconds behind in second place – even though he had crashed, remounted and rode with a rubbing brake until he could change his bike. So for the first time the Tour De France was won by an American. And, as Hinault said when he began to prevaricate on his promise to support Lemond, the race did decide who the strongest rider was although no doubt he felt sure the verdict would be in his favour. Hinault retired at the end of the season, as he said he would, and went on to devote his life to his farm in Brittany and various duties connected to the Tour De France. And France still awaits another French hero.

It remains to be seen how the 2013 Tour will pan out between Wiggins and Froome. The 1986 Tour is reckoned by many to have been the best ever. It might be too much to hope that the 2013 event will surpass it. Wiggins’ recent statements are not much different from some of those of Hinault when he was changing his mind about not defending his yellow jersey and riding for Lemond. It will be interesting to see how the media and public take sides. There isn’t the nationalistic factor this time – they are both British and ride for an England based team. However, Wiggins is our hero and it is hard to see media and public sentiment swinging behind Froome. Froome was born and brought up in Kenya where he has spent most of his life before coming to England in 2007 and subsequently joining Team Sky. He aims to return to Kenya in due course as a coach to encourage the development of cycling there. This rather tenuous and legalistic connection with Britain of course will not dampen our enthusiasm for him if he produces the goods. Wiggins is a Londoner brought up by his English mother’s parents in Maida Vale, near Kilburn. However, he was born of an Australian father in Ghent, Belgium before coming to London at the age of 2 with his English mother when his father, a track and six day rider of some talent but a propensity wine, women and song, abandoned them.

It remains to be seen how the 2013 Tour will pan out between Wiggins and Froome. The 1986 Tour is reckoned by many to have been the best ever. It might be too much to hope that the 2013 event will surpass it. Wiggins’ recent statements are not much different from some of those of Hinault when he was changing his mind about not defending his yellow jersey and riding for Lemond. It will be interesting to see how the media and public take sides. There isn’t the nationalistic factor this time – they are both British and ride for an England based team. However, Wiggins is our hero and it is hard to see media and public sentiment swinging behind Froome. Froome was born and brought up in Kenya where he has spent most of his life before coming to England in 2007 and subsequently joining Team Sky. He aims to return to Kenya in due course as a coach to encourage the development of cycling there. This rather tenuous and legalistic connection with Britain of course will not dampen our enthusiasm for him if he produces the goods. Wiggins is a Londoner brought up by his English mother’s parents in Maida Vale, near Kilburn. However, he was born of an Australian father in Ghent, Belgium before coming to London at the age of 2 with his English mother when his father, a track and six day rider of some talent but a propensity wine, women and song, abandoned them.

Whatever happens, it promises to be a fascinating season next year with a great deal of interest no doubt being shown on how Wiggins and Froome fare in their training and early season events leading up to the Tour De France. Will Wiggins win the Giro? If he does, will this make him more determined to go for the double? Will losing it make him even more determined to win the Tour? What circumstances may lead to him honouring his seeming promise to Froome? As things stand at the moment, my prediction is that he will defend his jersey with Brailsford’s blessing, but I’m not putting money on it.

For full stage by stage results of the 1986 Tour De France and a fairly detailed blow by blow account see the entry in the very useful Bike Race Info web site 1986 Tour de France. Even better, read the highly recommended Slaying the Badger: Greg LeMond, Bernhard Hinault, and the Greatest Tour de France by Richard Moore, 2011.

The other big happening is the televised confession of Lance Armstrong with Oprah Winfrey. He has admitted to blood doping and using other banned substances for all 7 of his Tour wins and even before his cancer. He said he didn’t think of it as cheating as it was just part of the job, like putting air in your tyres and water in your bottle. He also claimed it was not cheating as it was a level playing field, implying that all his other main opponents were at it too. More will come out as a result of this I’m sure. The interview and confession have had a very mixed response so far. Armstrong wants to be able to return to competition in Iron Man events but he will have to spill a lot more before his lifetime ban is reduced. Nicole Cooke’s take on Armstrong is powerfully expressed in her

The other big happening is the televised confession of Lance Armstrong with Oprah Winfrey. He has admitted to blood doping and using other banned substances for all 7 of his Tour wins and even before his cancer. He said he didn’t think of it as cheating as it was just part of the job, like putting air in your tyres and water in your bottle. He also claimed it was not cheating as it was a level playing field, implying that all his other main opponents were at it too. More will come out as a result of this I’m sure. The interview and confession have had a very mixed response so far. Armstrong wants to be able to return to competition in Iron Man events but he will have to spill a lot more before his lifetime ban is reduced. Nicole Cooke’s take on Armstrong is powerfully expressed in her

Perhaps the most remarkable stage of that year’s Tour was the stage 18 which climbed the Galibier and Croix de Fer before finishing at the top of the notorious 21 hair pins of L’Alpe d’Huez. Hinault and Lemond finished side by side in the same time, Lemond apparently pushing Hinault over the line to take the stage victory as a (perhaps rather ironic) thank you.

Perhaps the most remarkable stage of that year’s Tour was the stage 18 which climbed the Galibier and Croix de Fer before finishing at the top of the notorious 21 hair pins of L’Alpe d’Huez. Hinault and Lemond finished side by side in the same time, Lemond apparently pushing Hinault over the line to take the stage victory as a (perhaps rather ironic) thank you.

It remains to be seen how the 2013 Tour will pan out between Wiggins and Froome. The 1986 Tour is reckoned by many to have been the best ever. It might be too much to hope that the 2013 event will surpass it. Wiggins’ recent statements are not much different from some of those of Hinault when he was changing his mind about not defending his yellow jersey and riding for Lemond. It will be interesting to see how the media and public take sides. There isn’t the nationalistic factor this time – they are both British and ride for an England based team. However, Wiggins is our hero and it is hard to see media and public sentiment swinging behind Froome. Froome was born and brought up in Kenya where he has spent most of his life before coming to England in 2007 and subsequently joining Team Sky. He aims to return to Kenya in due course as a coach to encourage the development of cycling there. This rather tenuous and legalistic connection with Britain of course will not dampen our enthusiasm for him if he produces the goods. Wiggins is a Londoner brought up by his English mother’s parents in Maida Vale, near Kilburn. However, he was born of an Australian father in Ghent, Belgium before coming to London at the age of 2 with his English mother when his father, a track and six day rider of some talent but a propensity wine, women and song, abandoned them.

It remains to be seen how the 2013 Tour will pan out between Wiggins and Froome. The 1986 Tour is reckoned by many to have been the best ever. It might be too much to hope that the 2013 event will surpass it. Wiggins’ recent statements are not much different from some of those of Hinault when he was changing his mind about not defending his yellow jersey and riding for Lemond. It will be interesting to see how the media and public take sides. There isn’t the nationalistic factor this time – they are both British and ride for an England based team. However, Wiggins is our hero and it is hard to see media and public sentiment swinging behind Froome. Froome was born and brought up in Kenya where he has spent most of his life before coming to England in 2007 and subsequently joining Team Sky. He aims to return to Kenya in due course as a coach to encourage the development of cycling there. This rather tenuous and legalistic connection with Britain of course will not dampen our enthusiasm for him if he produces the goods. Wiggins is a Londoner brought up by his English mother’s parents in Maida Vale, near Kilburn. However, he was born of an Australian father in Ghent, Belgium before coming to London at the age of 2 with his English mother when his father, a track and six day rider of some talent but a propensity wine, women and song, abandoned them. I’m currently reading Tyler Hamilton’s ‘The Secret Race’ that gives the low down on his time with the US Postal professional cycling team and Lance Armstrong. The focus of the book is the doping regime their top riders used to win the Tour De France, particularly the use of EPO. They employed the notorious Dr. Michele Ferrari as their coach and doctor. What I found interesting is that the use of EPO was a part of the training and racing regime but the underlying science and other aspects of the training programme, innovative at the time, are now the orthodoxy. Minus the illegal drug use, the Ferrari training programme informs nearly all scientific training programmes today. It’s all about maximising certain numbers. Whether this is done within or without the rules, everyone is chasing the same numbers. One number that is a prerequisite to winning the Tour De France is that you must be able to sustain a certain power output, measured as wattage. The figure you need to achieve is 6.7 watts per kilogramme body weight. So for me to win the Tour De France at my present weight my threshold wattage would need to be 670 watts. Since Bradley Wiggins’s is something like 450 watts the problem is obvious. Assuming mine is about 200 watts, I would have to weigh about 30 kilos, 4 stone 10 oz. to achieve a figure of 6.7 watts per kilogramme.

I’m currently reading Tyler Hamilton’s ‘The Secret Race’ that gives the low down on his time with the US Postal professional cycling team and Lance Armstrong. The focus of the book is the doping regime their top riders used to win the Tour De France, particularly the use of EPO. They employed the notorious Dr. Michele Ferrari as their coach and doctor. What I found interesting is that the use of EPO was a part of the training and racing regime but the underlying science and other aspects of the training programme, innovative at the time, are now the orthodoxy. Minus the illegal drug use, the Ferrari training programme informs nearly all scientific training programmes today. It’s all about maximising certain numbers. Whether this is done within or without the rules, everyone is chasing the same numbers. One number that is a prerequisite to winning the Tour De France is that you must be able to sustain a certain power output, measured as wattage. The figure you need to achieve is 6.7 watts per kilogramme body weight. So for me to win the Tour De France at my present weight my threshold wattage would need to be 670 watts. Since Bradley Wiggins’s is something like 450 watts the problem is obvious. Assuming mine is about 200 watts, I would have to weigh about 30 kilos, 4 stone 10 oz. to achieve a figure of 6.7 watts per kilogramme.

For readers not familiar with tubular tyres, or tubs, they are similar to conventional wired-on tyres in that they have an outer casing with a tread attached to the circumference that contacts the road, and an inner tube that can be inflated to high pressures within. The main difference is that the outer casing is also a tube with the edges meeting at the inner circumference where they are stitched or otherwise fixed together.

For readers not familiar with tubular tyres, or tubs, they are similar to conventional wired-on tyres in that they have an outer casing with a tread attached to the circumference that contacts the road, and an inner tube that can be inflated to high pressures within. The main difference is that the outer casing is also a tube with the edges meeting at the inner circumference where they are stitched or otherwise fixed together. A tape runs round the inner circumference to cover the stitches or join. The inner tube is made of much lighter and thinner material than a conventional inner tube (it never has to come into contact with tyre levers). The construction method enables much lighter weights compared with wired-ons and can be inflated to much higher pressures – typical clincher 100 to 130 psi, tubs up to 200 psi. This makes them much faster and livelier for racing, less rolling resistance and less inertia to spin them up. The other advantage is they are generally quicker to replace when one punctures as it is just a matter of ripping the punctured one off and pulling a new one on. In a club road race it was normal to carry a spare tub folded behind your saddle for a quick swap and chase, assuming you had remembered to carry a pump too.

A tape runs round the inner circumference to cover the stitches or join. The inner tube is made of much lighter and thinner material than a conventional inner tube (it never has to come into contact with tyre levers). The construction method enables much lighter weights compared with wired-ons and can be inflated to much higher pressures – typical clincher 100 to 130 psi, tubs up to 200 psi. This makes them much faster and livelier for racing, less rolling resistance and less inertia to spin them up. The other advantage is they are generally quicker to replace when one punctures as it is just a matter of ripping the punctured one off and pulling a new one on. In a club road race it was normal to carry a spare tub folded behind your saddle for a quick swap and chase, assuming you had remembered to carry a pump too. The wheel is also different in that the rim is designed to fit the inner circumference of the tub. The tub is fixed into the rim by using a wider adhesive rim tape or, as we used to do, apply tub cement or glue to the rim well. Once inflated to a high pressure the tub grips the wheel very tightly and, if properly fixed, they rarely come off. Even so, on hot days and with a lot of front wheel braking, the glue can soften and the tub roll off the rim. And on the track where very light tubs are used at very high pressures it is not unknown for a tub to explode. However, compared with the other risks of racing, these risks are relatively minor and unusual. Wheels fitted with these rims were referred to as ‘sprints’ – hence sprints and tubs. We used to cycle out to events with an old set of sprints and tubs on the bike, or winter wired-ons, but carry our best wheels either side of the front wheel on sprint carriers to use in the race.

The wheel is also different in that the rim is designed to fit the inner circumference of the tub. The tub is fixed into the rim by using a wider adhesive rim tape or, as we used to do, apply tub cement or glue to the rim well. Once inflated to a high pressure the tub grips the wheel very tightly and, if properly fixed, they rarely come off. Even so, on hot days and with a lot of front wheel braking, the glue can soften and the tub roll off the rim. And on the track where very light tubs are used at very high pressures it is not unknown for a tub to explode. However, compared with the other risks of racing, these risks are relatively minor and unusual. Wheels fitted with these rims were referred to as ‘sprints’ – hence sprints and tubs. We used to cycle out to events with an old set of sprints and tubs on the bike, or winter wired-ons, but carry our best wheels either side of the front wheel on sprint carriers to use in the race.